This article is an updated version of one originally published in issue #30 of Roctober magazine. Although Maye never expressed his reaction to its publication to me directly, the fact that he wrote the publisher asking to buy a stack of copies told me all I needed to know. (His money not being good there, his order was filled gratis.) Maye died on July 17, 2002 of liver cancer, at age 67.

|

|

|

promotional headshot |

Anyone who has listened to any of the numerous "baseball

music" anthology albums that have appeared over the years can only

but agree that "baseball music" is a major-league contradiction

in terms. Whether it's lame novelty songs about the game, ballplayers

posing unconvincingly as pop singers, or all those John Fogerty and Queen

songs blasted incessantly at the ballparks, baseball and music have long

made for a couple of very uncomfortable teammates.

![]()

But, as with any rule, there is the rare exception, and the happiest one

by far to the baseball/music problem is Arthur Lee Maye: major league

outfielder in summertime, rhythm and blues singer come winter.

![]()

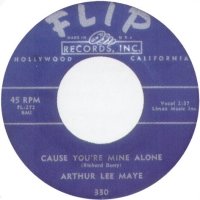

From the mid-1950s until the early '70s, Maye was simultaneously a good-hitting

outfielder with the Braves, Astros, Senators, Indians and White Sox, and

a top-flight vocalist with releases on Modern, RPM, Specialty, Dig and

Cash. There have been other men who roamed the outfield alongside Henry

Aaron, and others who sang the "di-di-di"s behind Richard Berry

on the original "Louie Louie", but only Arthur Lee Maye managed

to do both in a single lifetime.

![]()

Maye was no athlete turned weekend-warrior pop star. When it comes to

the recording studio the likes of Shaquille O'Neal and Bronson Arroyo

are but hobbyists, whereas Maye was serious - serious about baseball and

serious about music, in equal measures. Perhaps more importantly, he was

also equally talented at both. His career baseball numbers of 1109 hits

and a .274 batting average speak for themselves, but to gauge his musical

assets you'd have only to avail yourself of any of his many recordings.

Whether belting out gutbucket R&B or crooning emotional ballads, his

singing was always deft and authoritative. In either field, Arthur Lee

Maye was the real thing.

![]()

I interviewed Maye, by telephone, in a series of three

sessions beginning on Martin Luther King Day, 2001. He turned out to be

as genial, courteous, sober and proud as his photos had led me to expect. But, at

66 years old, he had no reason to pull his punches, and so he began the

conversation by addressing my dual-career question with a

bold proclamation. "I feel that I am the best singing athlete that

ever lived. I'm not bragging, it's just a fact". Absolutely agreed,

and, quite frankly, there remains to this day little chance of anyone

successfully rebutting the claim.

![]()

Although I was teeming with questions about each of his careers separately,

what I most wanted to know was how he juggled the two. Did one career

enhance the other? Did he favor one over the other in his heart? Was time

management a problem? And, most pressing of all, did his baseball teammates

hit him up for free copies of his records?

"Baseball was my first love", Maye told me, but that preference may have had a pragmatic basis to it. "I always said I could sing at 50, but I couldn't play baseball at 50". While he gave baseball the edge in his mind, the evidence shows that music didn't exactly take a back seat in his time allotment. He started his singing career at Jefferson High School in South Central L.A., a hotbed of musical talent that is alma mater to a long list of jazz and R&B greats. At the same time that major league scouts were taking notes on his diamond exploits, Maye was also running with a crowd that would "all go doo-wopping up and down the halls". Following a brief stint as a charter member of a nascent version of The Flairs, Maye co-founded a quintet called The Carmels. While they never got around to recording, The Carmels belonged to a scene that, although most of its members were still in school (Jefferson, as well as others), was already making records the magic of which endures to this day. This contingent included Cleve Duncan, leader of The Penguins; Alex Hodge, a founding member of The Platters; his brother Gaynel Hodge of The Hollywood Flames and The Turks; Curtis Williams of The Hollywood Flames and The Penguins; Obie Jessie, who went on to have a fine solo career under the name Young Jessie; Cornell Gunter, an original Platter and early-edition Coaster; and the now-legendary Richard Berry.

|

|

|

1965 |

After graduation Maye was drafted by the Milwaukee Braves, but in early 1954,

before setting out to play for their farm club in Boise, he entered a

studio to cut his first record. Teaming up with Berry and bass singer

Johnny Coleman to form The "5" Hearts (with the "5"

in ironic quote marks, a wink to the fact that there were only three of

them), Maye recorded "The Fine One", on which he dueted with

Berry, and "Please Please Baby", with Berry taking the lead.

The disc appeared on Flair, a subsidiary of Modern, L.A.'s premier R&B

label. The following year the same group recorded again for Flair, this

time as The Rams. The resulting single paired "Sweet Thing",

a raucous group-sing over barrelhouse piano, with "Rock Bottom",

a beat number on which they made like a hopped-up Ink Spots.

![]()

Around the same time as the second Flair recording was a session, credited

for the first time to The Crowns, that went out on Modern proper. Maye

took the lead on the A-side, the street corner blues "Set My Heart

Free", while Berry provided one of those mid-song basso profundo

soliloquies that was quickly becoming something of a signature for him.

"I Wanna Love", a mambo, announced Maye as an important new

lead voice, a likable and identifiable presence ideally suited for the

featured role. Already in place at this early date is a subtle plaintive

lilt at the ends of many of his lines, a trait which could easily have

lapsed into gimmick but which Maye would use with discretion and grace

throughout his career, turning it instead into a welcome trademark of

his own.

![]()

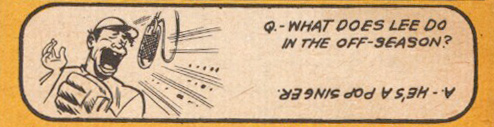

Maye was rising up the ladder in music just as he was in baseball. The

problem, though, was one that could have been spotted from afar: he could

only concentrate on music during the winter months, when baseball was

in its off-season. Maye reflected that such time-sharing held him back.

"When I was playing baseball all the requisite hours, I was a year

behind in music, and I never got a chance to catch up with the music trend

that I should have been with. I truly was behind the time, and I acknowledge

that. Baseball and singing collided".

![]()

The Braves elevated Maye steadily through their minor league ranks, and

he tore the joint up at each stop along the way. Rarely hitting below

.320, from Boise his ascent took him to Eau Claire, Yakima, Evansville,

Jacksonville, Wichita, Austin and Louisville (there being a whole lot

more minor leagues in that pre-expansion era than today). These small

cities were not exactly thriving centers of the jive, yet Maye still managed

to coax the furtherance of his musical education from them, and other

like podunks he'd pass through on the team's bumpy bus tours. "I'd

watch all of them, any entertainer when I was in a town. You learn from

each other. My stage presence wasn't polished, so I'd go to learn how

to get my stage presence from the other top guys who did it for a living".

Given the preponderance of night baseball, it would be almost impossible

to pull off this kind of candle-burning today.

|

Most of Maye's best recordings were made during his minor league years,

with a revolving lineup of Crowns, often including his brother Eugene

Maye, behind him. RPM, another label from the Modern combine, knocked

out a succession of fabulous singles by Arthur and The Crowns in 1955,

highlighted by back-to-back L.A.-area hits "Truly" and "Love

Me Always", the Treniers-like "Loop De Loop De Loop", and

"Please Don't Leave Me", an enchanting ballad. The following

year Maye and his group moved over to Specialty, where they made "Gloria",

a rhythmic doo-wopper with a sublime chanted refrain, and its flip, the

rollicking "Oh-Rooba-Lee". ("Cool Lovin'", one of

Maye's finest rockers, was done at this same session, but went unreleased

at the time.)

![]()

The group next appeared on Johnny Otis' Dig label, where under Maye's

name alone they did "This Is The Night For Love", a Maye original

with some radiant falsetto parts, coupled with the uptempo "Honey

Honey", featuring a stunning Mickey Baker-styled guitar solo. Following

the end of the 1956 baseball season Otis convened a veritable all-star

team of L.A.'s top harmony vocal talent, including Maye, Berry, Mel Williams

of The Shields and the reigning king of the L.A. rhythm and blues scene

(and fellow Jefferson alum), Jesse Belvin. Billed as The Jayos (for Otis'

initials), the group recorded a stellar album of covers of recent R&B

hits. The Jayos' versions of such tunes as "Earth Angel", "Only

You", "Gee" and "One Mint Julep" approach the

excellence of the originals, and the fact that Maye was chosen from among

that mighty heap of talent to sing lead on most of the songs stands as

a de facto tribute to his abilities and versatility.

![]()

Although the quality was certainly present, none of these nor any of Maye's

other releases became national hits. Besides the time-lag problem, Maye

believed his records were underpromoted. "I think the guys that recorded

me didn't take advantage of what they had. I don't know if they knew they

had a good product or not. If they had got out and worked the record …",

he trailed off.

|

|

1965 (flipside detail) |

Nineteen-fifty-nine was a watershed year for Maye. Batting .339 with 17 homers for the Braves' top farm club in Louisville, in mid-July Maye finally received his call-up to the big club in Milwaukee. It was an eye-opening experience, in more ways than the obvious. "I never saw a major league game until I played in one", Maye recalled (although until 1958 big-league ball had yet to reach further west than St. Louis). His two singles for Cash in that year turned out to be not only his last releases for any of the important L.A. R&B labels, they were also his last with The Crowns.

|

They were also, however, among the best records of his career. "Will

You Be Mine", a Maye composition, is highlighted by the Crowns' oohs

and aahs harmonizing with a tinkling celeste, creating a uniquely beautiful

effect. Flipped with a remake of "Honey Honey", slower yet even hotter

than the first rendition, the record was released after Maye's call-up

to the majors. Consequently, the artist credit on Cash's label read, "Lee

Maye of the Milwaukee Braves". Not only was this the only time his

alternate career was pointed out on one of his record labels, it was also

one of the few records credited to the baseball variant of his given name.

Why was he "Arthur Lee Maye" in music yet "Lee Maye"

in baseball? Maye himself couldn't explain the distinction. "I don't

know. I have no idea". It certainly didn't help him commercially.

"A lot of people maybe didn't know that Arthur Lee Maye was Lee Maye

singing", he said. Maye's final release for Cash coupled his own

soaring, majestic "All I Want Is Someone To Love" with "Pounding",

a throbbing rocker that climaxes with a seamless swoop upwards into a

chilling falsetto.

![]()

Maye hit an even .300 in 51 games with the Braves in 1959. Coming off

two successive appearances in the World Series and with three future Hall

of Famers on the squad, the Braves that year finished second in the National

League, two games behind the Dodgers, the eventual world champions. Alas, Maye's rookie

season would be the closest he'd ever come to winning a pennant. The following

year he was hitting above .300 again, yet was sent back to Louisville

for more seasoning. There he clobbered the ball once more, and in 1961

was brought up to the majors to stay.

![]()

Playing baseball in America's major league cities also served to give

Maye access to a more professional music circuit. "I met a lot of

dynamite singers. I sat in with James Brown, I met Sam Cooke. I knew Joe

Tex, Jackie Wilson. I worked with Little Willie John. Entertainers recognize

each other. I worked the Apollo in New York, and that was one of my biggest

moments. I had a ball. When I opened a show up in L.A. we had Billy Stewart,

Barbara Mason, The Exciters. Jerry Butler headlined the show. It was a

thrill for me just to be up with those guys, all of them had hit records".

![]()

Just as he was now singing with bigger names, he was likewise playing

alongside some of the biggest stars in baseball, particularly the future

home run king. "Henry Aaron doesn't get the credit he deserves, I

don't care what anyone says", Maye responded upon the introduction

of Aaron's name. Without either of us mentioning that it was Martin Luther

King Day, Maye segued into the issue of racism in baseball. "Let's

face the facts, we still got some of that slave mentality. I don't make

no bones about that. If Hank Aaron had been white he'd have been the greatest

thing that ever picked up a baseball bat". No dispute there, beyond

pointing out that Willie Mays did come close to that level of veneration.

Perhaps Aaron's due acclaim was inhibited by an additional factor. "And

if he'd have played in New York he'd have been the greatest. In Milwaukee

you didn't get that kind of press".

|

|

|

1968 |

Maye also played with Tommie Aaron, Hank's younger brother. I had

misremembered Tommie as being an outfielder, and asked Maye if he ever

filled out an outfield with the two Aarons. "Tommie was a first baseman.

He was one of the best first baseman, one of the best glovemen you'd ever

want to see". I brought up the name of another Brave, pitcher Lew

Burdette, who had capitalized on a 1957 World Series in which he thoroughly

manhandled the Yankees by cutting a smoking little country boogie number

(and Cowboy Copas cover) called "Three Strikes And You're Out"

for Dot. Did Maye ever get to hear Burdette's record? "Oh, shit",

he chuckled, but didn't elaborate whether he was referring to the record,

or to Burdette himself.

![]()

Maye broke through in a big way in 1964, the one season of everyday

playing time he would enjoy in his big league career. In 153 games he

hit .304, with 179 hits, 96 runs and a league-leading 44 doubles. But

early in 1965, after another strong start and on the verge of full-fledged

stardom, Maye injured his ankle, and upon his recovery was dealt to the

Houston Astros. The move to the cavernous Astrodome didn't do much for

his batting numbers, but, with Houston offering a much hotter R&B

climate than Milwaukee, it did bring new focus to his music career. He

landed a management deal with Huey Meaux, who set Maye up with more regular

gigging than he'd ever done before. An engagement at the Dome Shadows,

a Houston club, was an auspicious one, however. The joint's name was clearly

a reference to the Astrodome, then brand-new and, as the world's first indoor stadium, billed as the Eighth

Wonder of the World. Astros owner Judge Roy Hofheinz sued the nightclub's

owner, M.M. Stewart, over his use of the word "dome". Stewart

responded with a $1 million countersuit, and booked Maye in part to thumb

his nose at Hofheinz. "What I do after the curfew is my own business",

Maye was quoted at the time, thumbing his own nose a little in the process.

![]()

Meaux also cut a slew of studio sessions on Maye. The bulk of them emerged

early into the pair's contract, with a sequence of exceptional singles,

in the backwoods soul vein perfected by Arthur Alexander, released on

Jamie throughout 1965. Other records during the next few years were sporadic,

with scattered singles on Tower, Pacemaker, ABC Paramount and Buddah.

"When you're playing baseball and singing it's a very tough career

for both of those", Maye told me, "because you have to be at

both places at the same time of the year, and you can't do that".

|

1968 (flipside detail) |

Besides limiting the chance to cross-promote his two careers, being "Lee

Maye" in baseball came back to bite him in another way. In 1967 the

Reds brought up a slugging first baseman named Lee May, creating some

confusion between the two, with an especially nettlesome episode standing

out. "In Houston this girl claimed she had a baby for me", Maye

recalled. "But it wasn't, it was the other Lee May. My wife got ahold

of the story, but we got it straightened out". Unable to maintain

a grudge (although still not exactly laughing about the matter), Maye

said that once he met the "other" Lee May, "we became good

friends".

![]()

Before the 1967 season Maye was traded to the Cleveland Indians. He spent

the rest of his career in the American League, playing a season or two

apiece with the Indians, Senators and White Sox as a platoon outfielder

and pinch hitting specialist. In Washington he encountered another memorable

figure. "I played my next to last year for a guy I really respected,

Ted Williams. I thought he was the greatest hitter that ever lived in

baseball, but as a manager he was a bastard. He didn't give a shit about

nobody". Maye's stats for the A.L. phase of his career were as consistent

as they were respectable, averaging 325 at bats, a .275 batting average

and nine home runs a year. (A line-drive hitter, Maye clubbed only 94

homers during his 13-year career.) He hit .281 in 1968, the Year of the

Pitcher, when Carl Yastrzemski led the league batting just .301.

|

|

1970 |

After a .205 season in 1971 in Chicago, Lee Maye's baseball career came

to a close. Just as the beginnings of his twin careers coincided, so too

did their endings. "I quit music for a while. I had all kinds of

contract trouble with certain people, and after my baseball career I didn't

sing for a long time". He had a country single on the obscure Happy

Fox label in 1976, and a release for R&B revivalist Dave Antrell's

eponymous label in 1985, but that was about it. In the '90s Maye was rediscovered

by the Doo-Wop Society of Southern California, but by the

time I caught up with him his once-dynamic singing voice had been silenced.

"It's been gone about five or six years. I have high blood pressure,

and the medication I take for it makes me hoarse. I can't hit those pretty

high notes that I used to hit". Yet he took solace for his inability

to croon any longer in the music that he did sing when he could. "Everything

gets old, everything grows. But the records don't get old".

![]()

Playing and recording when he did, Maye wasn't able to sock away gazillions

of cabbage leaves during his years as a professional entertainer. After

his simultaneous retirements, he spent the next 20 years working for Amtrak.

"I worked at [L.A.'s] Union Station. I did everything there was to

be done at Amtrak, and I enjoyed it. I retired four years ago". He

held no resentment for the exhorbitant incomes earned by latter-day ballplayers.

"I'm glad they're getting all they can. Timing is the greatest thing

in a person's life, and you only play the game for a short while".

He kept an eye on baseball, and the man who faced Gibson, Tiant and Koufax

(not to mention Blue Moon, Mudcat and Catfish) insisted that Pedro Martinez,

then with the Red Sox, was greater than all of them. "That guy's

got the best stuff I've ever seen".

![]()

Unusual for musicians of his era, Maye's hobby was collecting records,

especially those of the vocal harmony groups. Rarer still, he said he

owned a copy of all of his own records, although some of them he had to

rebuy in later years. And while he couldn't literally wail 'em any more,

"every song I recorded I can sing to you today".

![]()

Richard Berry, who died in 1997, held a special place in Maye's life,

personally as well as professionally. "We were real, real tight.

We never had a cross word. The songs I didn't write for myself he would

write, and just about every record I made he sang on. Any song that Richard

would write, he'd call me and ask, 'Hey, is this a good song for anybody?'

He would play it, I would sing it, and he'd use me as the judge of the

song. Richard was one of the most talented people you'd ever meet, and

more than that he was a great friend".

![]()

As befit a lifetime .274 hitter who sang on the original "Louie Louie",

Arthur Lee Maye reflected back with satisfaction. "I have a wonderful

life, and I enjoy people listening to my music. I never dreamt that people

would still be playing them old funky records today. It's a thrill".

No regrets, although perhaps wishes. Given the advent of digital technology,

where a singer can literally phone in a performance and have it sound

as clean as if he were there in the studio, time-management in a pursuit

of joint careers today is much easier than it was in Maye's heyday. "If

I was playing baseball today, and the way I can sing, I would be double

dynamite!" Hits of both kinds.

![]()

Thanks for their help in the preparation of this article

go to Eric Predoehl, Bob Hulsey,

Miriam Linna and Billy Miller, Marv Goldberg,

Steve Propes, Jim Dawson, Mike Brown,

James Porter, Jake Austen and, of course,

the great singing athlete Arthur Lee Maye.

See also:

http://www.vocalgroupharmony.com/lee_maye.htm

http://www.electricearl.com/dws/ALmaye.html

http://www.astrosdaily.com/players/interviews/Maye_Lee.html

http://home.att.net/~marvart/Flairs/flairs.html

http://www.roctober.com/roctober/leemaye.html

http://www.rockabilly.nl/references/messages/arthur_lee_maye.htm

PRESENTED BY THE SPECTROPOP TEAM