|

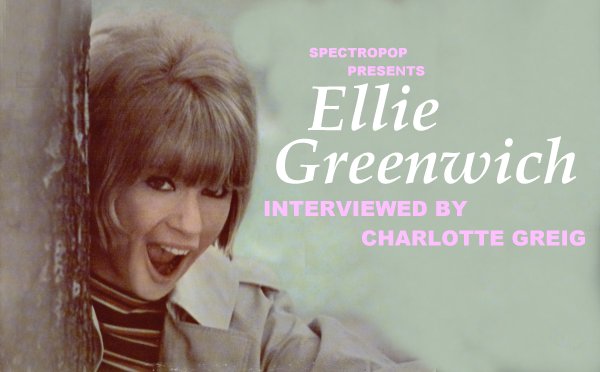

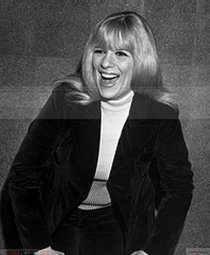

CHARLOTTE:

In the '60s, there were three husband and wife songwriting

partnerships that were really big, and you were one of them

with Jeff Barry. The others were …

ELLIE:

… Mann & Weil and Goffin & King.

CHARLOTTE:

What was it like working like that, with your husband?

ELLIE:

When things were working, and you're really connecting, what

could be better? Here's the person you're in love with, and

you're being creative together, and things are going well

- it's the highest high you can imagine. However, when there

were disagreements, it was very hard to leave it at the office

and go home at night and change hats: "Hi honey, what

do you want for dinner?" Jeff and I both got very involved

in studio work, and we were putting in the same hours. We'd

finally get home from a long day's work at the office - writing

the songs, rehearsing the groups, going in the studio - we'd

get home and you'd be hungry. You tell me, who's gonna cook

the meal? It wasn't like I was home all day, waiting for him:

"Here's your little dinner, dear." There became

some problems. It wasn't like, the man is the breadwinner,

and this is what you do. There was some rub there with Jeff

and I for a while, but we worked it out. It is hard to leave

things in the office when they don't go well.

CHARLOTTE:

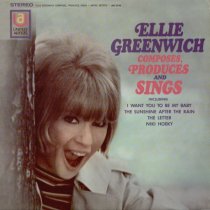

You and Carole King both made solo albums. She did incredibly

well with hers …

ELLIE:

… I didn't wanna record. I absolutely did not want to

record. But with the advent of 'Tapestry' doing so well, labels

were calling me left, right and centre, saying, "Ellie,

you've got to record." I'm not stupid, and after a while

I thought, "I have to take one of these offers."

But I wasn't up to it; I didn't have an image for myself.

I knew I didn't want to perform, and you had to, at that time.

The 'Let It Be Written, Let It Be Sung' album did so-so over

in England and in Europe, but not here. I did a tour - just

interviews, all over the country here, and I went over to

Europe, England, France - the whole thing. I went out on the

road to promote it, but I lip-synched because I was petrified

to do anything live.

Also, at that time, I opened up a jingle production company,

and was doing fairly well with jingles. That can be healthy

money, when you are writing jingles and singing on them. The

residuals can be kinda nice. I thought, "Let me get away

from records, and start a whole new thing." I did that

for a while, but towards the end of '72, into '73, I fell

apart. I guess you could say I had a nervous breakdown. I

left the business for a little over two years. When I came

back into the industry, I thought, "Let me get back into

background singing, I'm so happy on microphone. I could pretend

I was in a girl group, get a couple of other girls, have a

good time. I inched my way back into the things I wanted to

do. Then I started writing again. I had some records with

Ellen Foley, then got involved with Cyndi Lauper. Slowly,

I found my way in.

CHARLOTTE:

You were also involved with Blondie, weren't you?

I just talked to Alan Betrock about 'Out In The Streets',

one of their first demos.

ELLIE:

Yes. As a matter of fact, I had gotten tapes in from Alan

on this new group he had, Blondie. Really, those demos weren't

done particularly … well. I hate to say it on microphone,

but this is the truth. Debbie did have a look, but I opted,

unfortunately for me, not to get involved. Surely, there they

were several months later, becoming the biggest thing since

sliced bread. I sang on their first album, a lot of background

stuff, and on some songs on the 'Eat To The Beat' album. We're

sort of friendly-ish today, we keep in touch.

Cyndi Lauper's stuff has a '60s edge also, although she doesn't

wanna see it that way, because she doesn't wanna be dated,

so to speak. 'Girls Just Wanna Have Fun' could have been 1960s,

if you took those synthesizers out. Cyndi Lauper is a great

singer. She can really handle mostly any kind of material.

I had a song that was the B-side of 'Girls Just Wanna Have

Fun', a thing called 'Right Track, Wrong Train'. And I sang

background on her first album, and her most recent album.

CHARLOTTE:

You also wrote some songs for Nona Hendryx.

ELLIE:

In the early '80s, I started writing with a guy named Jeff

Kent, who was with a group called Dreams and a group called

Pierced Arrow. We wrote some things that were a little more

guitar oriented, a little heavier. I'm very close friends

with Nona and her manager, Vicki Wickham. Nona was getting

ready to record and asked me if I had any stuff. She came

over. Jeff Kent and I had written this song called 'Keep It

Confidential', which really had more of a country slant to

it, than R&B. It was an attitude kind of a song. Nona

loved it. We wrote the song with Ellen Foley, who used to

be with Meatloaf. It was supposed to go on her album, but

Nona took it, rearranged the whole thing, and it came out

as a single. That did so-so. Then we got together, and she,

Jeff and myself wrote a couple more things that went on her

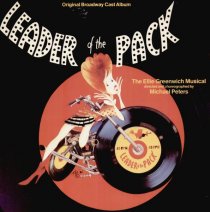

last couple of albums. Then 'Leader Of The Pack' happened

in '83.

CHARLOTTE:

How did that show come about

ELLIE:

Some friends of mine own the club The Bottom Line in New York

City. I'd always go there to see different shows. I had taken

a break from writing for a while in the '70s. I started to

write again, and a lot of the acts that were recording my

songs - such as Nona Hendryx, Karla DeVito and Ellen Foley

- were doing shows at The Bottom Line, so I would go see the

shows. For years, the owner, Alan Pepper, would say, "Why

don't you do a show here?" I'd say, "No, no, I don't

perform." Also, I was really petrified. It wasn't that

I wasn't interested. Late in '83, I'd gone down there to see

a show, and Alan took me aside. He goes, "I'm really

serious, I wanna do a show with all your music. I'd love you

to be in it, but if you don't wanna be in it, just talk about

it. We'll see what we can pull together." I figured,

what the heck? So we got together and we did this little show.

A friend of mine came in and wrote a little script, just to

get from one song to the other, a little story about me and

my music. They sort of convinced me to be in it. So I took

a deep breath - for two or three nights that wouldn't be so

bad. This was in January of '84. We had two shows a night.

The response was phenomenal. Some people from Broadway came

down and thought it might be a great idea to take to Broadway.

We re-ran the show for a month, April 27th through May 27th

of the same year, down at The Bottom Line, to wonderful reviews.

We were sold out all the time. It was terrific.

Then we moved on to Broadway, which, unfortunately, became

very problematic. The show ran for five months, but there

were a lot of internal problems with the producers - the usual

business stuff that goes on. There was really no vision for

the show. It's kind of a hybrid. It's rock'n'roll, and Broadway

doesn't really readily accept rock'n'roll. It worked better

in a smaller club. It might have worked well on Broadway if

they'd have stuck to a musical revue format, with a few anecdotes

about the time and myself. They didn't quite get a book musical

out of it, and it wasn't really quite a rock'n'roll revue.

The vision was lost. The book people didn't know how to respond,

nor did the rock people. Had there been more of a vision,

and some money put into advertising, we could have run. Because

the audiences loved it. They love the music; it's a proven

thing.

CHARLOTTE:

You've got a good voice, and you're not a shy person, so why

did it take you song long to want to get out there and perform

on stage?

ELLIE:

Well, I'm not shy, but I am. I don't consider myself as having

a good voice. I have what they call a "sound". I

did want to perform in the '60s, but I was married at the

time, to Jeff Barry, with whom I wrote a lot of hits. He didn't

feel that I should perform, because we were very busy writing

for all the groups that were recording our songs. We were

also producing records. He just felt that we were doing so

well writing and producing that to start a career as an artist

might have hurt that, which it probably would have. Being

married, and being from that time, I felt that this is what

my husband wanted, so I opted not to perform. I didn't mind

saying no. He was never emphatic, "You mustn't do it."

We talked about it, and I tended to go along. As the years

went on, the more I thought about doing it, the more I got

scared. The more you don't do that, the harder it is to even

consider it. So it left my mind.

So when this thing happened with 'Leader Of The Pack' at The

Bottom Line, I figured it was only six shows, I could bring

all my friends, you know, never expecting what happened to

happen. So I went from really doing nothing to The Bottom

Line to Broadway, which is kind of strange. In one respect,

the show was one of the most thrilling things that ever happened

to me, but it was also one of the worst, because of all the

BS that goes on.

CHARLOTTE:

In the '60s, when you were making all those records, there

was a big split between the songwriter and the artist, which

is something that's changed. How do you feel about that change?

ELLIE:

You mean that the artist would be the artist, and they would

take outside songs from independent songwriters, whereas today

the artists write their own thing? As a songwriter, it was

much easier in the '60s, when there was an artist who just

sang. There was a huge market and a need for the independent

songwriter. As a matter of fact, when the British Invasion

came here it greatly hurt. Here came all these self-contained

groups that wrote their own material and played their own

instruments, the whole thing. We wondered what we were going

to do with our music. We had to find our own artists to record

as vehicles for our material. It was great for those people

that wrote their own stuff and recorded it, but the independent

songwriter did suffer.

But it was at the time of the British Invasion that I discovered

Neil Diamond. A music publisher called me in to sing some

demos of some songs this guy had written. I'm there singing

these songs, doing these demos, and I said, "Who are

you?" He told me he was Neil Diamond, and that he'd had

a record out on Columbia. I thought his songs were kind of

interesting. I told him I'd like to hear more things. This

was in '65. I told him that I'd like my husband to hear some

of his songs. Jeff said we were kinda busy, that we wouldn't

have time, but we had him come in. Neil came in and played

us a bunch of songs. I loved the way he wrote and Jeff liked

his voice. So we went to a very dear friend of ours, Bert

Berns, may he rest in peace, who ran Bang Records at the time,

and we said, "We have this guy, do you want to hear some

things?" He heard a couple of songs and goes, "Here's

some bucks, go in and cut 'Cherry, Cherry' and 'Solitary Man'.

So we opened a company with Neil Diamond called Talleyrand

Music, and we co-published all his music with him. We salaried

him, weekly, and Jeff and I produced all his early hits. We

now had our own self-contained artist, who wrote his own material,

and sang it, and we were the producers.

CHARLOTTE:

Do you think overall in pop, it's been a good development

to have these singer-songwriters, or not?

ELLIE:

I think if you're good, it's great to be able to write your

own music and perform it. Because I don't think anyone's gonna

feel it the way you do. In that respect, creatively speaking,

if you're talented and can write some good stuff and perform

it, that's terrific. But for those that aren't that good,

I think it's a terrible thing.

CHARLOTTE:

What happened after Neil Diamond?

ELLIE:

Jeff and I were divorced right during that interim period.

That took me quite a long time to get over. It wasn't just

the marriage going, it was the career also - a double whammy.

Plus, divorce was not overly accepted. It was a major catastrophe.

So I had to deal with my family. At that time I got involved

with a guy named Mike Rashkow and we opened up a company called

Pineywood. But my head was nowhere. For close to six years,

I just didn't care what happened. I made a couple of records,

I did this, I did that. But my bubble was burst. My dream

was shattered, never to be really put back together again.

I had a very hard time.

CHARLOTTE:

These days, every person is expected to contribute more than

in those days, when you could be a great songwriter, but not

really have a great voice.

ELLIE:

Back in the '60s, there really were compartments. Everyone

had their own little spot. There was the record label. There

was the music publisher. There was the songwriter. There was

the record producer. There was the artist. They all had their

little jobs. Most of the time, those jobs did not overlap.

Nowadays, people publish their own music. The business has

grown so that people are much smarter on the business level.

There's a lot of money to be made in publishing, or producing

records. As technology has advanced, it's made it so much

easier to produce records. Once again, I think if the talent

is there, I see no problem whatsoever with everything crossing

over. It was a little easier in the '60s when everyone did

know their place, so to speak.

CHARLOTTE:

Of course, there were people like Phil Spector and, to some

extent, Carole King and yourself, who fulfilled all those

functions really.

ELLIE:

Spector, of course, wanted to do all those things by himself.

People like Carole and myself happened to come into an industry

as songwriters, but we also sang, didn't have bad voices,

and would make demonstration records of the songs we wrote.

Often those demos really came out great. The publisher would

hear it and think it could be a record. They would go to a

record label and the label would put it out. A case like that

was a group called the Raindrops, but there really wasn't

a group, it was just myself and Jeff doing all the voices.

We did this demo for a group called the Sensations, who'd

had a hit with 'Let Me In', (sings) "Let me in, wee-oo,

oop wee-oo". We wrote a song called 'What A Guy' that

we thought would be a great follow-up for them. We went in

and made the demo. The publishers heard it and thought it

could be a record. But there was no group. Back then, a lot

of labels put out what they called dummy groups. We'd throw

a few people together, go out and lip-synch the records, but

there really wasn't a group called the Raindrops. (In such

cases, the record company) would want to know who produced

the record? Well, Carole King produced it, she was in the

studio doing whatever, or Jeff and I were in the studio doing

it. We sort of came in the back door. We didn't think about

being producers, it just sort of happened to us. Whereas someone

like Phil Spector wanted to have his own label, wanted to

write, wanted to produce, wanted to control everything.

CHARLOTTE:

In those days you had arrangers. Now you have a songwriter

and a producer, and in the more kind of adult music you still

have arrangers. Do you have still have arrangers in ordinary

rock music?

ELLIE:

Back in the '60s we used arrangers, which we still do today.

Very often arrangers are used for their ideas, to some degree,

but very much to notate what's to be played. Sometimes a songwriter

hears an entire record in his head, but doesn't want to take

the time, and is probably not that well equipped, to write

down all these parts. So they'll hire an arranger, pay him

whatever, and have him arrange a session. With bands, they

jam all the time, and the arrangement happens. With a solo

artist who does not have a band, you have to have musicians

play something. Very often the producer, the songwriter and

the arranger will sit down and just brainstorm, but the arranger

will notate it.

CHARLOTTE:

When you went into the business, did you have the technical

skills, or were you just a new green person?

ELLIE:

I was a new green person, Charlotte. (Laughs) I played piano

well enough to write my songs. I do not consider myself a

good musician. I have very good musical instincts, but I would

never hire myself for a recording session. I was signed to

Leiber & Stoller - very big record producers and songwriters.

At one point they said, "We really ought to have a lead

sheet for this song." I sat there for hours counting

- one and two and - and I wrote these notes down. I learned

out of fear how to write my own lead sheets. I knew timings,

I knew what the notes were, I knew what to do, but I had never

really applied it. I think a lot of songwriters are kind of

lazy. If your main forte is songwriting, you don't really

wanna be bothered with the other stuff. So you hire an arranger.

CHARLOTTE:

Did you come from a musical family?

ELLIE:

My dad was a painter, and he sang a little bit and played

guitar, balalaika - he was of Russian descent - mandolin,

and all that stuff. He had some talent. My mom loved the arts.

She tried to sing, but not too well. So no, my family was

not overly musical.

CHARLOTTE:

What kind of family was it? Where did you live?

ELLIE:

I was born in Brooklyn. At the age of ten we moved to Levittown,

Long Island. We lived on the corner of Starlight and Springtime

Lane. My birthday is October 23rd, on the cusp of Libra and

Scorpio. My father was Catholic and my mother was Jewish.

I was destined for something - half and half, and on the cusp

of everything.

CHARLOTTE:

How did you find it as a woman in the music industry?

ELLIE:

When I first came into the industry, in the middle of 1962,

most of the women were background singers, or they were lyricists.

There were very few women who played piano, wrote songs, and

could go into a studio, work those controls and produce a

session. I wasn't your typical after-singer, as we called

them, who could go in and read that piece of music on the

stand, do 17 songs in three hours, boom-boom-boom. It was

a whole different thing. I'd go in, think of the background

parts, and put them down myself. I learned about overdubbing.

Back then they'd call me the Demo Queen. Many different publishers

would hire me to record demos of other writers' songs.

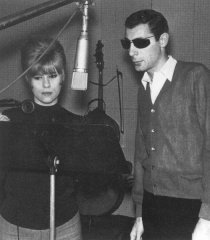

As a matter of fact, that's how I first met Dusty Springfield.

Every time somebody wrote a song for Dusty - they thought

of all the singers in New York at that particular time, I

sang closest to her - publishers would hire me for a nominal

fee to go into the studio; we'd run down the song, they'd

have a little band there, and I'd sing all these demos. Dusty,

when I first met her, said she had all these demos. She'd

wondered who the girl was singing on them, so they finally

told her. When she came here I was hired for one of her sessions

to sing background. So there we were stood on microphone,

looking alike - I tried desperately to sing exactly like her,

because she's one of my idols, vocally - and we've been friends

ever since, which is kinda nice.

CHARLOTTE:

In those days there was a hierarchy, where the artist is at

the bottom of the pile. Then you get the songwriter and the

producer. Would you agree with that?

ELLIE:

Fortunately, there was a grouping of us songwriters that was

able to make a career out of it. But there were people who

had one or two hits and then went into obscurity. They had

a rough time. But we were fortunate enough to be able to sustain.

I believe it was timing, luck, and our stuff was accepted.

Back in the '60s there were many small record labels - such

as Red Bird, Bang Records, and so on - that offered you the

opportunity to run up there and say, "Listen to this

song." There was a spontaneity that happened. The doors

were a little easier to walk through. A record label would

give you a shot to go out and produce a single. No more. The

single is no longer happening. It's always album, album. The

business has grown. It used to be called the MUSIC business.

Now it's the music BUSINESS. These days artists do publish,

do produce. The artist is real powerful nowadays. Back then

they weren't. If a songwriter had three or four things in

a row that made it, they had some power. The artist might

have been on the bottom rung in the '60s, but not today.

CHARLOTTE:

A lot of the girls, the artists, who I've spoken to say that

they were exploited. Would you agree with that?

ELLIE:

Yes, absolutely. I don't know what happened business-wise

with groups I was involved with, such as the Ronettes, the

Crystals and the Shangri-Las. I was not a record label, so

I don't know what kind of deals were made, what kind of money

they got. I wrote the songs, I rehearsed them on the songs,

I would sometimes co-produce a record with them, but as a

rule, I didn't know what their deal was. But very often they

were not paid the high royalties. In the late '50s and very

early '60s, those girl groups never got royalties at all,

which is terrible exploitation. Even male groups, like Frankie

Lymon & the Teenagers, didn't get the time of day. They'd

get $50 to come in and do the session - "See ya, kids."

It's terrible. They're still fighting things like that today.

CHARLOTTE:

As a songwriter, did you get the publishing dues that you

should have had?

ELLIE:

This is a tough question. People say that, "We can't

believe that you don't own any of your songs." That's

sort of what happened then. You mention the word publisher

… I thought, "Wow, it's gonna be in print, these

people are publishers, like a book publisher." I didn't

connect that you could actually publish your own stuff. Everybody

was much smarter than we were, coming in as kids. They knew,

"Ooh, there could be money here in publishing."

The Leiber & Stollers, the Don Kirshners, they all had

their own publishing companies. And we were very grateful

to be signed to them and get a weekly little paycheque. We

always got our royalties. We got our writer's money, but never

really knew to ask or question - which wasn't really their

fault - about retaining a piece. I mean, I wish I had a little

piece of every one of those songs I have written.

CHARLOTTE:

So none of those songs actually belong to you, but you get

royalties?

ELLIE:

I get royalties as a writer. People say, "God, you were

so ripped off!" I wouldn't say ripped off. I just wish

that there were people around me at the time that said, "Before

you sign this contract, why don't you consider A, B or C?"

It didn't even enter my mind. There's a funny story: in the

'Leader Of The Pack' show: I had gone to Leiber & Stoller's

office, and they thought I was Carole King. I was waiting

for an appointment, and I was playing away on the piano. They

went, "Carole!" I went, "No, no, no!"

I was a nervous wreck. They heard some stuff I had written

and, within a month or so, they had offered me a job, writing.

They offered me $75 a week. I thought that was a funny number,

and I said, "No, a hundred, you have to give me a hundred."

They finally agreed, and I thought, "Wow! A hundred bucks

a week! I'm really flying high here! I have the publishing,

I have a little cubbyhole to go to every day and write my

stuff. Who knows who I'm gonna meet?" I will say one

thing, in defence of not being involved in the business -

monetarily, a stupid, stupid move, but on a creative level,

you weren't bothered with any of those problems. All you did

was come in and hone in on your craft - go in and write your

songs. It was a happy time. To me, so I didn't get $200,000,

I got $25,000 - it was fine. You didn't really think in those

terms. In hindsight, years later, I went, "Oh my lord!"

But who knew that the songs that Goffin & King, or Mann

& Weil, or Jeff and I were writing would continue to live

on? We just thought, "It's a hit - great!" You worried

about your next hit, and you went on, never thinking about

10 or 20 years down the line. We didn't know.

CHARLOTTE:

At the time, the way people thought was completely different.

Your songs, particularly your songs, I notice, centre an awful

lot around marriage, romance, idealism and all that. Why were

you writing those kind of songs?

ELLIE:

Well … I guess I was writing the boy/girl relationship

songs because I'm really a hopeful romantic. And I think they

work. That's what we got out there: boys and girls. Everybody

loves to be in love. Everybody hates it when things are going

wrong. You meet someone you've flipped over; you really want

it to work out. Perhaps take it all the way and get married.

Also, what happened was, you start writing songs, and you

start having hits with that kind of theme, and you don't wanna

tamper with something that's successful. You gear yourself

to stay in that area. As a matter of fact, in the middle '60s,

I started writing some "message" songs. They said,

"Ellie, give us another 'Da Doo Ron Ron'. Give us a 'Be

My Baby'." They almost expected a certain type of song

to come out of me.

CHARLOTTE:

Those songs were so young, so much to do with teenage life.

I think that that music is under-estimated. People like it,

but they see it as simplistic. Yet they don't see other music,

like Elvis or whatever, as something old fashioned.

ELLIE:

It's hard for me to relate to my music, because I did it -

that was the music I grew up with, that was my job, that's

what I did. You watch audiences, these young kids going 'round

loving 'Da Doo Ron Ron'. It's new to them. Yet you see this

other group of people, aged between 35 and 50, the baby-boomers:

it takes them back to another time, an age of innocence. They

recall their first love, look at their husband and say, "That

was our song." There's something very nice about that.

These songs were part of their lives, which is heavy duty,

it really is.

CHARLOTTE:

Then the music changed as the teenagers grew up, and the real

problems of life came in on them. Do you think there was also

something about American society that was changing? Now, you

come to America, and you don't get the feeling of hope and

that great sense of a new society doing something wonderful.

ELLIE:

What's going on in society always affects culture, what's

going on in the arts. I think, with the loss of innocence,

the Kennedy assassination, Vietnam, and all that happening

her, people got very cynical and very bitter. And, of course,

a lot of the music reflected that. However, the music that

would talk about that was a constant reminder of what was

going on out there, but there was this other grouping of musical

stuff that allowed you to escape. It's rough out there. I

would hate to be a teenager growing up today - afraid of nuclear

war, afraid of this, afraid of that, afraid of pollution.

Progress is wonderful, but boy, it can ruin some nice things.

CHARLOTTE:

At a certain point, these male groups appeared from England,

a lot of whom were doing covers of girl group songs. What

happened then? Why was there a sudden shift from girls to

boys? Or was that just chance that the Beatles happened to

be a male group?

ELLIE:

When you get phenomenons that happen, such as an Elvis Presley,

or the Beatles, I think an industry is in need of a change.

They'll pull out every single stop to make that happen. People

say, "Wow, thank goodness for the girl groups. [Without

them] what would have happened to your songs? I say, "Well,

maybe it wouldn't have been as tender, and had exactly the

same meaning, but I could've seen a boy group doing (sings)

'and then she kissed me.'" It just so happened that I

got involved working with Phil Spector, who had Philles Records,

and he happened to have girls - Darlene Love, the Crystals,

the Ronettes. We never even thought in terms of girl groups,

we just wrote a song. I think some of it was chance that the

male groups came. The girls were out there, it was happening.

Then came the British Invasion, a new look, a new sound -

we were ready for it.

CHARLOTTE:

Who were the fans of girl groups? Were they boys, or girls,

or both?

ELLIE:

I think both. The guys thought, "Oh wow, would I love

to be with her!" Then there were the girls who wanted

to emulate them. Also, the girl group songs were very universal

subject matter, and relatively simple. A lot of kids could

sing along. The fans were definitely mixed.

CHARLOTTE:

Looking back on it, the Shangri-Las and the Ronettes stand

out as girl groups who had a strong image. The other girls

were more goody-goody. Were they bad girls?

ELLIE:

Overall, the girl groups had very sweet images, except for

the Ronettes and the Shangri-Las, who had a tougher, harder

attitude. By today's standards, they were as innocent as the

day is long. Back then, they seemed to have a street toughness,

but with a lot of vulnerability. Mary Weiss [had] the sweetest

long straight hair, an angelic face, and then this nasal voice

comes out, and this little attitude - the best of both worlds.

Were they tougher than [say] the Dixie Cups? They were a little

harder. They also knew they had a look, and they played into

it. But if you blew too hard on them … "Waaaah!"

You'd say, "This is what you're gonna do" The most

they'd ever say was, "Well, we're not gonna do it."

Ten minutes later, they were doing it. That's as bad as they

got, if you wanna consider that bad.

CHARLOTTE:

In the '70s and the '80s, there were a number of people who

went back to that girl group sound, but in a more tongue-in-cheek

way. Was it meant tongue-in-cheek to begin with? I know you

were sincere about what you were doing. I think people think

that they've discovered a humorous edge in what was meant

in a very sincere, perhaps rather naive way in the '60s. But

when you look at what the Shangri-Las did, you can't believe

that it was 100% serious.

ELLIE:

OK, 'Leader Of The Pack' … believe it or not, 'Leader

Of The Pack' was serious. (Laughs) Back in the '60s, when

you started making money, a lot of people went out bought

motorcycles. We figured, "Ooh, we'll take a trend that's

happening, make a boy/girl love song, but let's give it a

sick element, let's have the guy die." It was like a

little soap opera. We wrote that song with a guy named Shadow

Morton. He wrote 'Remember (Walkin' In The Sand)', songs like

that. Now, they look at songs like that with a satirical edge,

but when we wrote it, we were serious about it.

CHARLOTTE:

A lot of feminists would feel that the songs you wrote - because

they were saying how wonderful marriage was, how great it

would be the day you got married and had babies - were oppressive

to women.

ELLIE:

I know people that have gotten married in the past two years

who have used 'Chapel Of Love' as their wedding song. I think,

no matter how much of a feminist one claims to be … Lord

knows, if you go by my songs, and the way my personal life

has gone, you'd say, "Oh my, this lady was dreaming."

It didn't exactly happen the way I was writing it. However,

I would have liked it to have gone that way. I am a very firm

believer in equality, women and men: if you can do the job,

by all means go ahead and do it. But I still feel it would

be nice if that romance can be there, birds could sing if

you fell in love, and you could hear violins. I think that

would be really terrific - I don't care how old you are, or

what generation.

Most of my famous songs were early to mid-'60s. Attitudes

starting changing in the late '60s, into the '70s. A lot of

people that I got involved with in the music industry - '70s

people, the next generation - would ask me, "What was

it like in the '60s? Were you really like your songs?"

I'd tell them that I came in right out of college, grew up

in a nice middle class family out in Long Island, got my degree

as a teacher, taught for three and a half weeks, and thought,

"Naah, I gotta try music. I'll always have this to fall

back on." I wanted a little house with a picket fence,

2.3 children. I really wanted that. That's what I had hoped

was gonna happen for me. To hear my stuff on the radio: "Ooh,

ooh, ooh, this is bliss, ultimate bliss." I really came

into the industry with the belief that if you work hard enough,

I could have a taste of that. But then, when my marriage did

fall apart … well, the disillusionment, you can imagine:

the person who wrote 'Doo Wah Diddy' and 'Chapel Of Love'

has gotta be devastated. I realised, those words, "'Till

death do us part", they don't really mean anything. Through

the good times and bad times - what happened to that? We're

having bad times - why should this be over? I think if Jeff

and I hadn't been so successful so quickly, and had taken

the time to grow together as people, and gotten to know each

other a little better … I knew him very well for the

year and a half we were dating, but then we got so busy in

the throes of the industry - writing, contracts, studios and

this and that - that the minute a personal problem came up,

we put it on the back burner. We didn't have time to work

out those things.

CHARLOTTE:

'River Deep - Mountain High' sounds like a more adult kind

of song. I read that you were breaking up with Jeff at that

time.

ELLIE:

We were already divorced. When we got divorced, because we

were such a successful writing team, we thought that for business

purposes, if people find out, fine, but let's not overly publicise

it. We got divorced right around Christmastime, December 13th,

but we'd already had all these cards printed, "From Ellie

& Jeff Barry." We just signed them, "Ellie &

Jeff", and sent them out. People found out as time went

on, but we were still working together, although we took time

off to clear the head. Phil had called Jeff about the three

of us getting together to write again, which we hadn't done

in a couple of years. We met at Jeff's apartment, and we had

to fill Phil in, "By the way, we're no longer together."

He was concerned if we could still write together. We said,

"No problem, we can certainly do it." Phil told

us it was for Tina Turner, and it would be a big departure

from what she had been known for. We sat down, I think over

a period of two days - now, we were all working individually,

Phil had started something, Jeff had started something, I

had started something - sat down at the piano and played the

things we had started. We pulled from all those things, and

out came 'River Deep - Mountain High'. It was like a little

potpourri of all the things we had been writing.

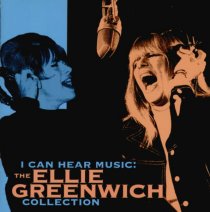

At that same writing session we also wrote 'I Can Hear Music',

which is kinda interesting: "This is the way I always

thought it would be." My, my, my, what's going on here?

I think the fact that I had now gone through a divorce - so

had Jeff, and Lord only knows what Phil Spector had been through,

and still goes through - gave a little edge to our writing.

Yet that hopefulness was still in there: "When I'm with

you, I can hear music, everything else disappears."

CHARLOTTE:

Are you still in touch with people like Jeff Barry, Phil Spector,

Leiber & Stoller?

ELLIE:

Leiber & Stoller I speak to occasionally, and see at certain

music business functions.

CHARLOTTE:

I read that they never really liked girl group music. They

thought it was … silly.

ELLIE:

Well, it wasn't the kind of stuff that they wrote, but I don't

think things like 'Yakety Yak' and 'Charlie Brown' were exactly

… hey! But they didn't have to get involved in that side

of things. They had signed writers, Jeff and myself, who took

very good care of that end of what was happening in the business.

They did very well financially from our songs.

CHARLOTTE:

What's going on with your career at the moment?

ELLIE:

My career's had some ups and downs, like everybody's has.

At the present time I'm starting to write again, which I haven't

done in quite a while. I've also opened up a jingle production

company - great name, it's called Hook, Line & Singer.

A guy named Steve Tudanger [1] and myself, we write and produce

commercials for radio and TV. Also, my manager Bob Weiner

and I have just recently acquired the stage rights for the

'Leader Of The Pack' show and we hope to get a tour out there

[2].

|