THE EARLY YEARS

"I vividly recall walking into my manager's office in Denmark Street and being greeted with the popping of corks and the news that 'You Don't Know' was No 1 on the charts. Another thing I particularly remember is John Schroeder and Mike Hawker presenting me with a gold chain bracelet with a gold disc for each one of their songs that I had helped to make hits." - Helen Shapiro

JOHN SCHROEDER was one of the great A&R men of the British pop music explosion of the 1960s. He began as Norrie Paramor's assistant at EMI Records - where he helped shape the careers of Cliff Richard and the Shadows, Helen Shapiro and others - before moving on to the Oriole and Piccadilly labels. Presently working on his autobiography, he took time off recently to tell me about his early days.

"I started to play the piano at school. I did five years of classical music. My brother went to the same school as me and he was good at just everything. At sport he was captain of this and captain of that. But the one thing he had no aptitude for at all was music, so I decided to go that route and learned to play the piano. I ended up winning the school music cup. I played 'Jesu, Joy Of Man's Desiring' and won the school cup. Then I got involved in buying pop song sheets and started playing those.

"I left school early because my brother was just too good. He was

younger than me and top at everything. I felt very pushed down, if you

like. Then my father sent me to Switzerland to a factory. The intention

was for me to learn the language, and find out a bit about engineering,

which I hated. A Swiss student came over to his firm - it was one of those

deals."

Finding funds tight in Switzerland, in his spare time John formed a trio and started playing Strauss waltzes to earn a bit extra money.

"When I came back my father told me I had to do national service. Then he said if I got articled to a firm of chartered accountants - that would be a good career for me, I'd get initials after my name, and all that. So he articled me to a firm of chartered accountants, which was a bad move for him, and a good one for me, because the firm had a lot of show business accounts. I ended up going to shows, concerts and all sorts of things - anything but studying accountancy. After two years of accountancy, and failing all of my examinations, I was out. My father told me that he couldn't do any more for me, and completely disowned me - he didn't want to know. My brother, on the other hand, went from strength to strength. He was a father's boy, if you like, and I was a mother's boy.

"My mother was an entertainer. She was a professional skater, very much into musicals and show business. So I wrote to all of the companies that dealt with music - people like the BBC and EMI Records - about ten of them, I suppose. I got one reply, from EMI. They told me that they didn't have a vacancy, but they would put my name on file, and if anything came up, they'd contact me. For six months, I was washing dishes at Joe Lyons and driving a van for the Victoria Wine Company, all these stupid little jobs. Then suddenly a letter came through the door. It was from EMI telling me that they had a position in the sales office in East Castle Street. That was my beginning with EMI Records.

"I was in the sales office for 18 months and learned all sorts of things: how to create a record catalogue, and all this sort of stuff, the mechanics of a record company. I was sent down to the factory and shown how records were made, pressed, and all the rest of it. Then one day, one of the A&R managers got an assistant. I think it was Norman Newell. He got an assistant called John Burgess. I thought, if one got one, another might get one. So I went and asked the managing director if any of the other A&R managers might be getting assistants. He asked me if that was the direction in the company I wanted to go. I said very much so. So he sent me for an interview with Norrie Paramor. I went up and saw Norrie and within ten minutes I had a job as his assistant. That was the real beginning of my career in music.

"Norrie Paramor was a fantastic boss. He became my mentor. He introduced

me to absolutely everybody - if he had a meeting with somebody, he always

introduced me. I was always invited to the recording sessions. He taught

me how to study a musical score, because he was a very good arranger.

He was a producer and a writer as well. Gradually, as I learned more,

he gave me more to do on my own initiative. Then he told me that he wanted

me to audition anyone new for him. I'd take them into the studio - this

was Abbey Road Studios, where we were based. Anybody who came in who wanted

to introduce us to a new artist, or hear demos, it was on my shoulders.

I took over that completely. I alleviated Norrie from a lot of those chores.

Also, I made appointments for him to see people like music publishers.

Or even the publishers would see me with any material they had for any

of our artists. Then I would pass it on to Norrie and tell him what I

thought. Gradually he gave me more and more responsibilities. I started

in East Castle Street. Then EMI moved to Manchester Square - a big glass

building. We were on the fourth floor, and I had my own office attached

to Norrie's. The studios were in Abbey Road. We commuted between the studios

and Manchester Square."

After working with Norrie Paramor for 18 months, John began to wonder when he would get the chance to do a session on his own.

"He'd taken me to every single session. I'd worked there in the studio with him and seen how it works. I'd gotten to know all the musicians, all that kind of stuff, but I hadn't actually produced anything on my own. There was a session booked one day for 7.30 in the evening. It was Pearl Carr and Teddy Johnson. Norrie was late, which was very unusual. We had Pearl Carr, Teddy Johnson, their manager, Dennis Preston, and a studio full of musicians. Time was going by and costing money. Then all eyes turned on me. That was it, I had to take over. That was my first session on my own. I was very scared and nervous. I turned to the engineer and said, "Do you think the strings should have more echo?" He said, "I don't know. You're the bloody producer!" That's what he said to me! No help from anyone! We did the session and then I went and mixed it on my own. I took the result back to Norrie. He listened to it and said, "Don't you think there should be more guitar?" I said, "No, quite frankly, it's as it should be." He said, "It's your record, so that's how it should be." It was released as it was and got to No 12 on the charts. The track was 'Sing Little Birdie'. That was my first production.

"I was with EMI for four years, and was with Norrie on every single session. I also went in the studio on my own and did some tracks with Cliff Richard and the Shadows, album tracks and things. Plus I found Tommy Bruce, who did 'Ain't Misbehavin'', and Frank Ifield, who did 'I Remember You'. A lot of these records obviously carry Norrie Paramor's name, because he was the boss. My name didn't appear anywhere, even though I was strongly instrumental in a lot of things that were done on our label, which was Columbia. We had at one time 40 artists, which is a hell of a lot of artists.

"I was in one night with Michael Holliday putting his voice on some tracks. He was a tiny guy, you know. Studio 2 at EMI was a very big studio with a control room above it. There was Michael all by himself down in the studio, and I was up in the control room having a joke with the engineer. He looked up at us and thought we were taking the piss out of him. He started getting very uptight. We were laughing, and he thought we were laughing at him, which was rather sad. Unfortunately, the following day he committed suicide. I was very, very upset about it, because I thought it was something that I had done. Everyone assured me it wasn't. He was very concerned about tax and things. He got himself in a terrible state and took his life. That was all very unfortunate.

"I found and discovered Helen Shapiro. I got a call one day from

a guy named Maurice Berman, who ran a school of music in Baker Street.

Maurice rang and said that he had a lot of pupils at his school, and would

I come in and give them some advice about recording - if I had the time,

it would help them. I was always doing things like that. I got down there

and told him to bring them in one at a time and have them each sing one

song. I'd write a report afterwards and tell him what I thought about

each one. There were about ten, girls and boys. He told me that he thought

there was one out of the ten that had exceptional talent, but he didn't

tell me which one it was. They all came in. When Helen's turn came she

sang 'Birth Of The Blues', I think it was. She sang it incredibly. She

had a very jazzy voice, a fantastic voice, very deep, like a boy. Her

tuning, her phrasing and her whole presence were extremely strong - right

in your face, I couldn't believe it! I told Maurice that they all had

possibilities, but there was one person who was better than any of them,

absolutely amazing, and that was Helen Shapiro. Of course, he felt the

same. I told him that I would get her a couple of songs to learn, and

she could come to Studio 2 at Abbey Road for an audition."

Having learned the two songs, Helen went to the studio to record a voice-and-piano demo.

"I got an acetate cut and told her that I would play it for Norrie. You had to catch him at the right moment. I didn't want to give it to him unless he was fully listening. I caught that moment and put it on the machine. Afterwards, there was a big pause. He said, "Mmmm, he's very good, isn't he?" I told him it wasn't a he, but a she, and she was 13 years old. He was totally flabbergasted.

|

(Helen Shapiro, Norrie Paramor and John Schroeder at Abbey Road.) |

"We got Helen in with her parents, and she was signed, but for six months we couldn't find a song for her. In those days, at 13 years of age, what could she sing? Songs about romantic love were a no-no. Exasperated, Norrie said that we'd had her under contract for six months, not made a record, and would be breaching the terms of the contract of we didn't do something with her very soon. He said, if we can't find a song, why didn't I try and write something for her?"

John had got to know and had written a couple of songs with Mike Hawker, who used to work in EMI's promotion department and was now writing for Jazz News. John played a tune for Mike, who thought it would be good for Helen and came up with the lyric for 'Don't Treat Me Like A Child'.

"I took the song to Norrie, played it to him. He thought it was very good. He got Helen in, and she liked it. Next thing you know we were in the studio recording it. I had written a tune that Eddie Calvert had recorded, but 'Don't Treat Me Like A Child' was the first actual song I ever had recorded.

"After the record got to No 3 on the charts, Norrie told me I had to write a follow-up. I asked Mike if he'd like to write the lyrics for the follow-up, and he said he'd love to. But could we think of anything? It was very hard. I had learned that the follow-up to a hit was always a problem. Should it be something like it? Or should it be something completely different? Whatever you do, someone says, "Oh, you should have done something more like the first one." Or, "You should have done something more different." I'd had a tune in my head. Whenever I went home, at about 2 in the morning, having been in the studio all night, I'd play the piano for about half an hour, to unwind. I lived with my parents then. I'd play this tune that was in my head. My mother absolutely adored it. She always sat there mesmerised by this tune. I told Mike about the tune in my head. He asked me to play it for him, which I did. He thought it was beautiful and wrote a lyric for it. We took it to Norrie, who thought it was very good. Helen recorded the song and we had an acetate made. Norrie had a close friend called Bunny Lewis, who was an agent. He called Bunny in and played the acetate for him. Bunny turned around and said, "Norrie, that is a No 1 record!" He was right. It was incredible. One morning alone it sold 45,000 records. I would say that 'You Don't Know' is the best song I've ever written. The song has a really strong meaning for me, because of its association with my mother.

"Worse was to come! We now had to write a follow-up to a No 1 record,

and Rank were going to make a 10-minute feature film about the record

being made, from beginning to end - a little documentary that went out

with a major film on the Rank circuit. Norrie told me it was the biggest

chance of my life, to have a film made about a song I had written - it

was an incredible opportunity, all that promotion. But I had to come up

with something really, really good. It was a Friday. He wanted it on his

desk by Monday morning!"

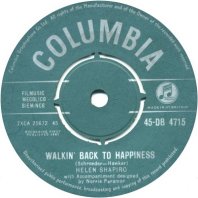

By now John and Mike Hawker had developed a good working relationship. John gave to Mike an acetate of a couple of new melodies on which he had been working. Mike chose a bright and bouncy tune and came back with a lyric to 'Walking Back To Happiness'.

"That ended up going to No 1 as well, and sold a million records. The song won Mike and I an Ivor Novello Award, which is the biggest award you can win as a songwriter. The song is now over 40 years old and is still played on radio and all sorts of TV things. The royalties are still very good on it after all this time. Helen has been singing the song all of her life. She called her book 'Walking Back To Happiness' as well. When the song reached the No 1 position I started to get offers. I was headhunted by a lot of record labels, including a little company called Oriole Records." (To be continued.)

|

|

|

[click each label to enlarge] | ||

|

|

|

JOHN SCHROEDER on CD: http://tinyurl.com/jv34k |

HELEN SHAPIRO on CD: http://tinyurl.com/oghwk |

|

||

click here for press release WITH THANKS TO SAMSKI | ||

PRESENTED BY THE SPECTROPOP TEAM |

||

|

|

||