Mambo

Gee Gee

THE STORY OF GEORGE GOLDNER AND TICO RECORDS by Stuffed Animal

PART

THREE:

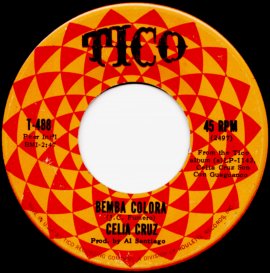

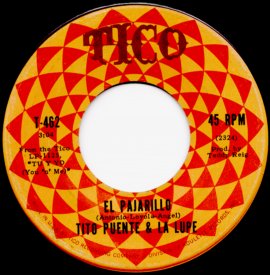

Az˙car Pa' Ti EDDIE PALMIERI, CELIA CRUZ & LA LUPE The pachanga dance craze had a tremendous impact on the sound of Latin New York, as evidenced by the large number of pachanga albums released during the early '60s, both on major and independent labels. The dance was a high-energy mix of merengue and cha-cha-chá rhythms. Flute-and-violin charanga bands dominated the scene, and none were more popular than those led by pianist Charlie Palmieri and percussionist-turned-flautist Johnny Pacheco. Both Palmieri and Pacheco recorded for Al Santiago's Alegre label, which would later be bought out by Roulette. However, for the time being, Alegre's artists were competition, and Teddy Reig had to keep his artists viable in the marketplace. Soon, he had signed charangas led by Rosendo Rosell, Pupi Legarreta, and Alfredito Valdés, Jr. Though Alfredito chose to abandon his solo career in order to join Machito's Afro-Cubans, his George Goldner-supervised album was so popular, it rated a reissue in 1969. Reig also revamped the orchestras of Machito, Pete Terrace, and Arsenio Rodríguez to fit the pachanga mould. The playing of flautist Mauricio Smith was prominent on most if not all of the recordings Tico cut during this period. He got to strut his stuff under his own name in 1963 on an album called Machito Presents Fluta Nova. Even Tito Puente, returning to Tico after a frustrating five years at RCA Victor, got a charanga-style makeover. His biggest contribution to the pachanga craze was a song that would outlive it: "Oye Cómo Va", introduced on his 1962 Tico album El Rey Tito, Bravo Puente! It would become his most lucrative copyright after Carlos Santana remade it as a Latin rock song in 1971. Despite Puente's later statements to the contrary, it was also a sizable hit in its original version. That said, another of Teddy Reig's new signings, Ray Barretto, cut the only hit single on Tico that most people remember from 1962. While New York's Latino population was twisting hips and waving red handkerchiefs to the rhythms of pachanga, the rest of America was caught up in teenage dance crazes like the Twist, the Monkey, the Mashed Potatoes and The Watusi. During this time, the pop charts were bursting with dance records by artists like Little Eva, Chubby Checker, Major Lance and Joey Dee and The Starlighters. Latin music was dance music, after all, so it made sense for Tico to try and cash in on the trend. However, Ray Barretto was the last person you would've expected to cut a pop record; he wasn't oriented in that direction at all. Like Joe Loco, he had as much jazz background as Latin, if not more. In the '50s, he'd played on dates with Charlie Parker, Max Roach, Cannonball Adderly, Herbie Mann and a host of other jazz greats. His conga playing was one of the major attractions on Tito Puente's final recordings for RCA Victor. He emerged as a bandleader in his own right in 1961, cutting pachanga music for the Riverside label. With his band, Charanga Moderna, he came to Tico the following year and scored big with his very first album. Noting the word "Watusi" in the title of one of the twelve tracks he'd cut, Teddy Reig chose it as the single, hoping that teenagers would take notice. They did, and it's not hard to figure out why. The record begins with the crack of handclappings at six-beat intervals while Alfredito Valdés, Jr. plays a wicked piano vamp. Then, like three hip Puerto Rican guys rapping on a street corner, Barretto's vocal group, consisting of Wito Kortwright on lead, with Pete Bonnet and Goody Basora on back-up, makes with some groovy Spanglish dialogue over a sizzling pachanga beat. That beat proved so irresistible, English-only speakers had no trouble being seduced by it. Clearly a precursor of rap music, but far more danceable than most rap records, "El Watusi" helped change its namesake from a line dance into a booty-wagging showpiece for go-go girls and beach bunnies. It broke Top Twenty on both the pop and R & B charts, sending Morris Levy and Teddy Reig into fits of sheer ecstasy. Unfortunately, it sent Ray Barretto into a state of confusion regarding his musical direction - so much so that he later expressed regret at having cut the song. He felt pressured to duplicate its success, and spent the rest of his time at Tico unsuccessfully trying to do so. However, over the course of four albums, Barretto made an important discovery: he didn't really like the sound of charanga bands! He added a brass section to his 1964 album Guajira Y Guaguancó, setting the stage for harder-edged recordings he'd begin making for Fania Records three years later. In 1963, Tico marketed twenty-two albums. Graciela got a long-overdue showcase as a featured artist on Está Es Graciela, an LP that exploits her twin talents for passionate bolero singing and spicy double entendre. Lest anyone fear she was leaving the Afro-Cubans for a solo career, Machito and Mario Bauzá were on hand to provide high-profile musical backing. Puerto Rican songstress and politician Ruth Fernández, Spanish show band Los Chavales de España and former Tito Puente sideman Willie Bobo joined the Tico family that year. Back from an extended gig in California where he and Mongo Santamaría had helped vibraphonist Cal Tjader tighten up his Latin chops, Bobo was already showing strong signs of evolving into the fusion artist he'd ultimately become. He and his jazz-oriented orchestra cut just one Tico album session (Bobo! Do That Thing/Guajira was his first as a bandleader) before moving on to Roulette, and then, Verve Records. There, Bobo waxed cult favourites like "Spanish Grease" and the original version of Santana's 1971 million-seller "Evil Ways". Motion picture and singing star Miguelito Valdés stayed a little longer. Signing him to Tico was certainly a coup for Morris Levy and Teddy Reig; one of the most successful and respected stars of Latin music, his career dated back to the late 1930s when he'd co-founded the influential Casino de la Playa Orchestra in Cuba. That group also gave the world Pérez Prado, the self-proclaimed Mambo King. After migrating to the United States, Valdés was a featured singer with the Xavier Cugat Orchestra and Machito's Afro-Cubans. During the heyday of American movie musicals, he had electrified the screen in films like Pan-Americana with his exotic Cuban/Mexican looks, open-shirted sexuality and bombastic conga drumming. Yet he was certainly more than a Hollywood pretty boy; his rapid-fire vocal improvisations were amazing, and when it came to the art of Afro-Cuban chanting, he had few equals. In fact, Valdés had introduced the form to American popular music in the '40s via Cugat waxings like "Babalú" (the original!) and "Ana Boroco Tinde". The opportunity to cut a reunion album with Machito brought him to Tico. He completed that LP, a solo album recorded in Mexico with El Mariachi Tenochtitlán, and another special project (which will be discussed later) before resuming his international touring and acting career. Pianist Eddie Palmieri came to Tico in 1964, just as Beatlemania began spreading through the land. The younger brother of Charlie Palmieri, he worked with Pete Terrace and Tito Rodríguez prior to forming his Orquesta La Perfecta and signing to Al Santiago's Alegre label. He rode the crest of the pachanga craze until Alegre went bankrupt. Then Morris Levy bought his contract, and his next scheduled Alegre album, Echando Pa'Lante, was issued on Tico Records. He remained at Tico until the early '70s, scoring his biggest hit with "Azúcar". At eight-and-a-half minutes, it was the longest Latin dance tune ever released as a 45 rpm single at that time. "It was a hit before I recorded it", Palmieri told writer David Carp in 1998. "I was already playing it all over town, in Brooklyn, at the Palladium, (so) when I recorded it, I had to record it the way we did it!" This presented Morris Levy with a challenge. Here was a hit waiting to happen, but it was far too lengthy by 1964 standards. However, he had an ace up his sleeve. One of the most influential jazz deejays in New York was "Symphony Sid" Torin, who hosted a Latin music show on WABC Radio. During the '50s, Torin had emceed numerous live broadcasts from Birdland; Levy knew him from those days. He called in a favour from Torin, and the deejay promptly put Palmieiri's song in heavy rotation. The response was overwhelmingly positive, and other radio stations soon followed WABC's example. "'Symphony Sid' took it to the hilt", Palmieri confirmed, "and I can never thank him enough for that, (him and) Morris Levy". Foremost among other jocks who pushed the record was Dick "Ricardo" Sugar, still loyally waving the Tico banner after fifteen years. Also popular in some R & B markets, "Azúcar" was the centerpiece of Palmieri's 1965 album Azúcar Pa' Ti (Sugar For You). His other Tico albums of note include the R & B-flavoured Justicia produced by George Goldner, Champagne featuring the funky "African Twist", Vamanos Pal' Monte with his brother Charlie as a musical guest, and a critically-acclaimed concert disc, 1972's Live At Sing Sing, recorded on site at the infamous prison with vocal accompaniment by the Harlem River Drive Singers. 1967's Bamboleate, recorded with Cal Tjader, was part of a special two album deal arranged by Morris Levy and producer Creed Taylor in which Palmieri was loaned to Tjader's label, M-G-M, so that the two could record another set, El Sonido Nuevo. Both LPs are highly regarded. Palmieri, who later became the first artist to win a Latin Grammy award, is noted for his tendency toward musical innovation. Over time, he became one of Latin jazz's chief exponents. His band included flautist George Castro, ace timbalero Manny Oquendo, singer Ismael Quintana and trombonist Barry Rogers, who, in the '70s, would earn a reputation as one of salsa's greatest arrangers. Morris Levy acquired the brightest jewel in Tico's crown when he succeeded in luring the great Celia Cruz to Tico in 1965. Famous since the early '50s as lead singer of Cuba's highly regarded brass ensemble La Sonora Matancera, she had defected with the band in 1960 in order to escape the Castro regime. After five years recording with La Sonora for New York's Seeco label, she decided it was time to pursue a solo career. However, after leaving La Sonora, her recordings lacked the consistently strong musical backing she was accustomed to. At Tico, she got just the sonic boost she needed - Tito Puente and His Orchestra. Their first collaboration, Cuba y Puerto Rico Son . . . (a reference to Cruz and Puente's respective ethnicities) won critical acclaim in New York and across Latin America, as did a dozen subsequent albums recorded with Puente, and with Mexican bandleader Memo Salamanca. The music was solid, but sales were not, and Cruz's time with Tico proved to be a bittersweet experience for her. "I made eight albums (for Tico) that went nowhere", she complained to Latin Beat Magazine years later. "Nobody was promoting them!" That's unlikely. Morris Levy was known as one of the best record promoters in the business. For some reason, New York Latinos weren't yet ready for what Cruz had to offer. Although she'd be proclaimed Queen of Salsa in the 1970s, she was not the most popular female act on the Tico roster during the '60s. That distinction belonged to La Lupe. A Cuban native who is barely remembered today in her homeland, La Lupe is also unknown to most North Americans. However, her name still inspires awe among a generation of Latin music lovers. La Lupe's approach to singing, and to life in general, was passionate in the extreme. "(She) was no ordinary singer", stresses John Ramos, a long-time fan. "Her performances, including shouts of Ahí na má (loosely translated, it means 'come closer to me, baby'), the kicking off of her shoes, the ripping of her clothes, pulling her hair, biting her hands and arms, beating herself and, at times, her musicians (!), laughing and crying while dancing onstage, were unforgettable!" Lupe herself was known to say, "In Cuba, they called me crazy". Many people in New York thought she was insane, too, but many others considered her an artiste par excellence who gave the most electrifying performances they'd ever seen. "(They) were always awesome", Ramos confirms. "She was described as a sado-masochist with a sense of rhythm". In order to experience the full impact of La Lupe, you had to see her in person, but one record comes close to capturing her dangerous sensuality: the malevolent rendition of Little Willie John's much-covered hit "Fever" that she waxed, as "Fiebre", for the Discuba label while she was still a resident of Cuba is like a volcano erupting, so . . . well, so feverish that it puts the Peggy Lee version to shame. Many believe it to be the definitive interpretation of the song. La Lupe re-cut "Fever" on her 1968 Tico album Queen of Latin Soul. Most Latin musicians of her era had extensive training in their craft. Lupe Victoria Yoli had no musical training, just a teaching certificate that she never used. Singing was her obsession - she wanted to be like Olga Guillot, a Cuban grand diva whose personality came across on stage as powerfully as her vocals did. After completing her teacher training, Lupe gravitated immediately to the entertainment world. She joined a group called Los Tropicubanos but couldn't get along with the other members, and was soon asked to leave. Her talent and desire for a singing career were both so strong, she managed to find success on her own. In 1959, she landed a nightclub gig singing rock and pop songs in Spanish. Her sets at Club La Red became the talk of Havana, and if they were even half as outrageous as they became in subsequent years, it's not hard to understand why. If legend is to be believed, La Lupe recorded an album called Con el Diablo en el Cuerpo (With The Devil In My Body), and then proceeded to act as if it were so. Her stage performances became so scandalous that Fidel Castro is said to have personally had her deported from Cuba! Whatever the truth may be surrounding her departure from the island, it's known that she made her way to New York in the early '60s and hooked up with fellow expatriate Mongo Santamaría. He and producer Orrin Keepnews were so taken with her raw vocal ability, they created an album to showcase her, calling it Mongo Introduces La Lupe. Released on the Riverside label in 1963, it caused quite a stir in the Latin music community, and led to bookings at such venues as the Apollo Theater and The Palladium.

Santamaría introduced her to Tito Puente, and much to his consternation, she began appearing exclusively with Puente's orchestra shortly thereafter. On the latter's recommendation and promise to join her in the studio, Morris Levy offered her a Tico recording contract in 1965. The first album release, Tito Puente Swings, The Exciting Lupe Sings, became one of the fastest-moving items in the catalogue, selling in excess of 500,000 copies, the equivalent of a platinum record in the Latin music world. The album's eclectic mix of pachanga, samba, pasodoble, merengue and bolero stylings showed off La Lupe's high-voltage vibrato to excellent effect. Three more Lupe/Puente collaborations followed and, for the next two years, polls declared her Latin music's most popular female vocalist. Both the bandleader and his new star vocalist had volatile temperaments, and this eventually ended their association; but by then, Lupe had enough of a fan base to sustain a solo career. Her Tico albums and singles were snatched up like twenty-dollar bills and, while the recordings had considerable merit, it was unquestionably her notorious reputation that initially made them sell. Her lifestyle, like her stage show, was extravagant - only the most ostentatious cars, jewellery, clothing and living quarters would satisfy her. La Lupe's flamboyance made her the first Latin singer to draw a large gay following, many of them young Puerto Rican males. Consequently, she became a sensation in Puerto Rico, especially after she exposed herself during an appearance on Puerto Rican television and was banned. She grew to be so famous in New York, she also was tapped to appear on North American variety shows like Merv Griffin and Dick Cavett where, presumably, her performances were less revealing. In addition to her striptease act and fits of physical violence, audience members might see Lupe fall into deep trances onstage. A devout follower of the Afro-Cuban religion known as Santería, she claimed to be in constant communication with Changó, Ochún, Yemayá and other orishas (saints). This supernatural aspect only added to the mystique that mesmerized her fans. Yet, her religious convictions were perhaps a little too intense: the ritual candles she lit each night twice burned down her home!

Picture research by Stuffed Animal,

Tony Rounce, Malcolm Baumgart, Richard Havers, Leonardo Flores,

Phil Milstein, Rat Pfink and Jeffrey Glenn.

|